Sylvia could easily have taken Otto’s premature death as a model for her own suicidal behavior, as the following lines from “Daddy” hint:īy saying she was ten rather than eight, Plath conflates the year of her father’s death and that of her own first suicidal gesture as revealed in Andrew Wilson’s book – although in “Lady Lazarus” she would allude obliquely to this “first time” as “an accident.” But the words “I made a model of you” may have a broader scope. When she tells her father “I made a model of you,” she seems to mean that Ted was a stand-in for the man she really desired, the way a model train is a replica of the original. For a poet who could write “I dream that I am Oedipus” (“The Eye-mote”) and blithely address her father as “bridegroom” (“The Beekeeper’s Daughter”), psychoanalyzing herself was easy – maybe too easy. Or rather “I do, I do” – as if she were wedding two men: not just Ted, but Daddy. She knew of his sadistic streak when she married him, confiding to a horrified mentor about his habit of “bashing people around.” But that didn’t stop her from saying “I do.” The man in black with the Meinkampf look was Ted Hughes, perennially decked out in his bohemian poet’s uniform: a regulation black sweater and black pants. But after the doctors “stuck me together with glue,” she writes, “then I knew what to do”: “Daddy” presents her first famous suicide attempt – the one described in her novel The Bell Jar – as an effort to be reunited with him. The most brutal thing Otto did in Sylvia’s eyes was to abandon her by dying early.

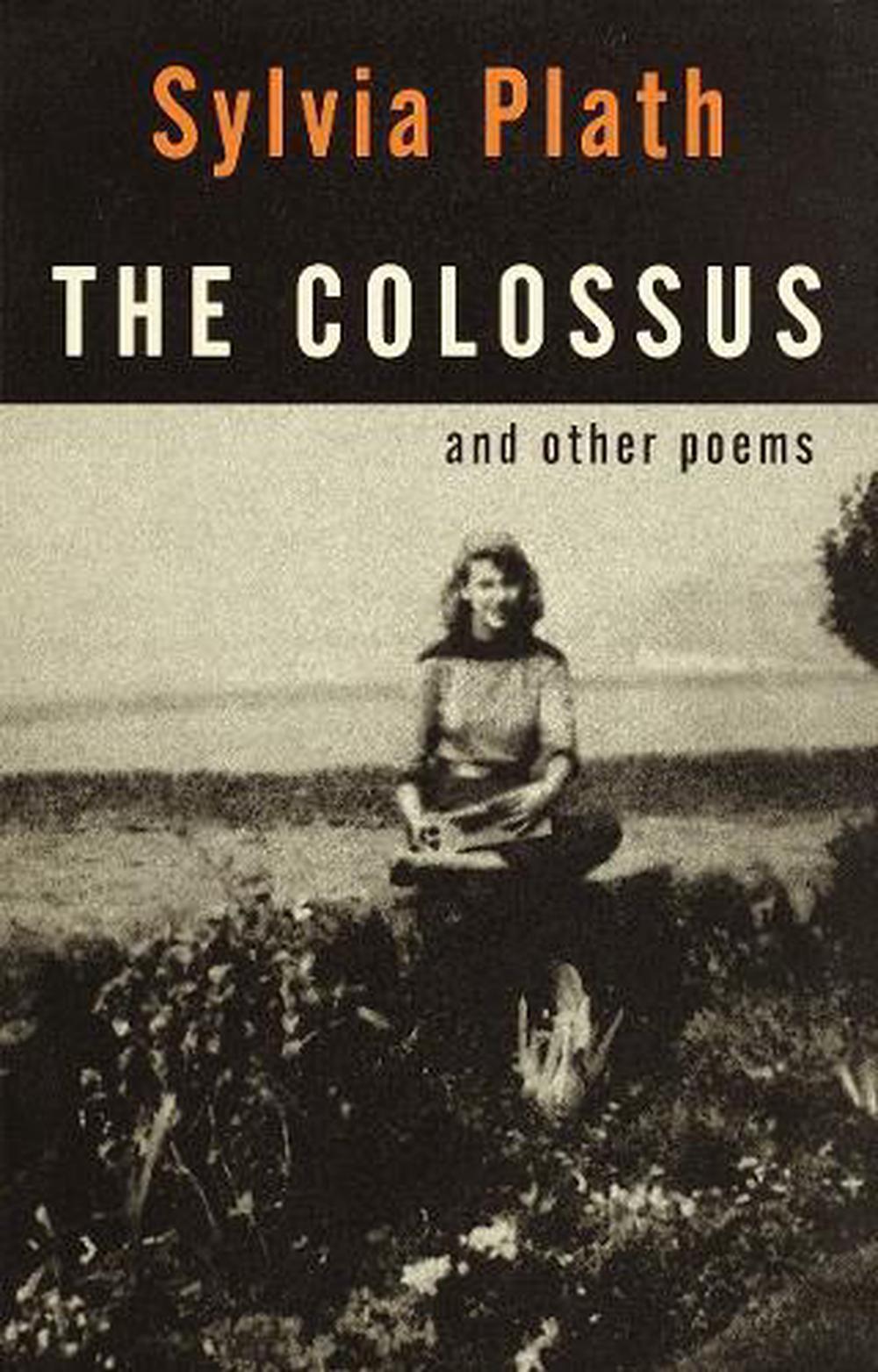

#The colossus sylvia plath skin#

To show off his disdain for the conventional prejudices that govern human behavior, Hayman writes, “he used to skin a rat, cook it and eat it in front of his students.” A hard-working, studious blacksmith’s son who immigrated to America as a teenager and forged an academic career teaching German and biology, Otto Plath was not a Nazi.īut he was an iron-willed domestic tyrant who subjugated Sylvia’s mother – a bright former student twenty-one years his junior – and may well have had a sadistic streak. In The Death and Life of Sylvia Plath, biographer Ronald Hayman suggests that she had actually worshipped her father when she was a little girl, doting on his praise. At least that is what the narrator says in this deliberately over-the-top poem. In fact, the line “Every woman adores a Fascist” comes from the poem “Daddy.” Her father is the jack-booted brute who bit her “pretty red heart in two,” the “panzer-man” who scared her with his “neat moustache” and “Aryan eye,” his Luftwaffe and swastika. Earlier biographies and the poems themselves suggest that she was traumatized at a tender age by her father’s death. In Mad Girl’s Love Song: Sylvia Plath and Life Before Ted, Andrew Wilson asserts that she had already tried to cut her throat when she was ten years old. But Plath’s suicide likely had much deeper roots. “The boot in the face, the brute/Brute heart of a brute like you.” To his accusers, Hughes was a brute who kissed the girls and made them die. “Every woman adores a Fascist,” Plath wrote in one of her most famous poems. Why did the women who were drawn to him take their own life? At the time, he was having an affair with a mutual friend who went on to commit suicide herself. The death of her father when she was eight left Sylvia Plath – in the words of her poem “The Colossus” – “married to shadow.” On February 11, 1963, Plath widowed her estranged husband, poet Ted Hughes, by committing suicide at age 30.

He has given us permission to publish his words:

Mark had thoughts about the Plath legend – with a Girardian twist. We’ve published a couple guest posts from anthropologist Mark Anspach ( here and here), and one Q&A about his new book, Vengeance in Reverse. The publication of Sylvia Plath’s last letters to her psychiatrist and other letters, too, has put the controversial Plath, one of the top American poets of the twentieth century, back in the news. Getting “back, back, back to you”: Sylvia Plath with her parents.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)